Grease Fire Fuel Apparently Missed

Receipt indicates exhaust pipe not cleared of grease before grease fire started.

The owner of Tai Ho Mandarin and Cantonese Restaurant has given city officials a receipt indicating that their system was cleaned prior to the fire. Firefighters have said grease buildup in that pipe fueled a grease fire last week that killed two Boston firefighters.

Industry specialists say a thorough inspection and cleaning two months before the fire would have revealed any buildup or leaks. They say the cleaning receipt points to an industrywide problem: National standards for the inspection and the cleaning of restaurant grease are weak, and state and local regulation of grease-cleaning companies in Massachusetts is virtually nonexistent. As a result, many companies inspect and clean grease only from visible areas – stoves, exhaust hoods, and walls, for example.

“This is, for the most part, a one-or-two-men-and-a-dog-and-a-truck kind of business,” said Steven Schlesinger, co-owner of Tri State Fire Protection and Tri State Hood & Duct, which cleans restaurants in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, including large chains such as Burger King. “There are people with a boom box and a pressure washer who go out there and say they’re hood-cleaning specialists. But it’s not as simple as that.”

A man who answered the phone at J&B Cleaning declined to comment, and the company owner, Joy Bell Tsui, did not return a message left with his son at the Claxton Street residence where the company is headquartered.

A woman who answered the phone listed for the president of the company that owns Tai Ho, Qi Chun Li, hung up on a reporter seeking comment yesterday.

National fire codes, which Massachusetts adopted several years ago as state codes with the force of law, require that kitchen exhaust ducts “be inspected for grease buildup by a properly trained, qualified, and certified company or person(s).” But the code leaves it to state and local fire officials to decide what qualifications, training, or certifications are necessary in each jurisdiction.

The receipt from Roslindale-based J&B Cleaning says its staff worked in the kitchen below and climbed onto the roof above to clean an exhaust fan. But it does not say they cleaned the crucial area in between – where fire officials say the hidden grease was leaking.

There is no indication on the June 21 receipt that the cleaners even examined the vent for grease buildup.

State fire codes mandate quarterly inspections of entire kitchen exhaust systems and the cleaning of any buildup found. The codes charge restaurant owners with the ultimate responsibility for making sure it is done right.

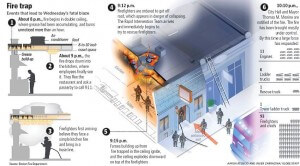

Fire Chief Kevin MacCurtain has said grease from the exhaust pipe oozed into a crawl space above a ceiling, where it ignited Aug. 29 and burned undetected for at least an hour before firefighters arrived.

September 7, 2007

The owner of Tai Ho Mandarin and Cantonese Restaurant has given city officials a receipt indicating that a company hired to remove kitchen grease at the West Roxbury eatery in June did not clean the kitchen exhaust pipe. Firefighters have said grease buildup in that pipe fueled a blaze last week that killed two Boston firefighters.

The receipt from Roslindale-based J&B Cleaning says its staff worked in the kitchen below and climbed onto the roof above to clean an exhaust fan. But it does not say they cleaned the crucial area in between – where fire officials say the hidden grease was leaking.

There is no indication on the June 21 receipt that the cleaners even examined the vent for grease buildup.

State fire codes mandate quarterly inspections of entire kitchen exhaust systems and the cleaning of any buildup found. The codes charge restaurant owners with the ultimate responsibility for making sure it is done right.

Fire Chief Kevin MacCurtain has said grease from the exhaust pipe oozed into a crawl space above a ceiling, where it ignited Aug. 29 and burned undetected for at least an hour before firefighters arrived.

Industry specialists say a thorough inspection and cleaning two months before the fire would have revealed any buildup or leaks. They say the cleaning receipt points to an industrywide problem: National standards for the inspection and the cleaning of restaurant grease are weak, and state and local regulation of grease-cleaning companies in Massachusetts is virtually nonexistent. As a result, many companies inspect and clean grease only from visible areas – stoves, exhaust hoods, and walls, for example.

“This is, for the most part, a one-or-two-men-and-a-dog-and-a-truck kind of business,” said Steven Schlesinger, co-owner of Tri State Fire Protection and Tri State Hood & Duct, which cleans restaurants in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, including large chains such as Burger King. “There are people with a boom box and a pressure washer who go out there and say they’re hood-cleaning specialists. But it’s not as simple as that.”

A man who answered the phone at J&B Cleaning declined to comment, and the company owner, Joy Bell Tsui, did not return a message left with his son at the Claxton Street residence where the company is headquartered.

A woman who answered the phone listed for the president of the company that owns Tai Ho, Qi Chun Li, hung up on a reporter seeking comment yesterday.

National fire codes, which Massachusetts adopted several years ago as state codes with the force of law, require that kitchen exhaust ducts “be inspected for grease buildup by a properly trained, qualified, and certified company or person(s).” But the code leaves it to state and local fire officials to decide what qualifications, training, or certifications are necessary in each jurisdiction.

In Massachusetts, there are no training, certification, or licensing requirements for grease-cleaning companies. State fire codes give authority over instituting such requirements to local fire departments. In Boston, no such requirements exist.

Boston fire officials declined to say why yesterday. “We’re going to let the investigation run its course before saying anything,” said Steve MacDonald, department spokesman.

The receipt for the Tai Ho cleaning, which cost $500, was provided to city officials by the owner of the restaurant, and the city provided it to the media.

The Globe reported last week that city health inspectors had not visited the restaurant for more than a year, even though state regulations require the city to inspect restaurants twice a year. Just after the fire, city officials rebutted allegations that there was any connection between the missed inspections and the grease buildup that fueled the fire.

Grease-cleaning specialists say most restaurants entrust inspections and cleaning to a single company. Typically, workers begin with a visual inspection of duct work, inside and outside. To detect leaks, they use a flashlight to look for grease accumulation at seams in the ducts.

If part of the duct is inaccessible or concealed within a crawl space, as may have been the case at Tai Ho, the workers are required to note that on their cleaning and inspection report, according to Scheslinger and fire prevention engineers at the National Fire Prevention Association, which issues the national codes adopted by Massachusetts.

It’s unclear whether the owner of Tai Ho maintained any inspection reports. It also is unclear whether the owner entrusted quarterly inspection as well as cleaning duties to J&B Cleaning. Based on statements from fire officials about the cause of the blaze, specialists said, grease should have been detected.

“If there was enough up there to burn for an hour, you would have seen some accumulation on the duct,” said Kathy A. Notarianni, head of the Department of Fire Protection Engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

At Tai Ho, however, there were two ceilings below the crawl space, and fire officials have said the grease buildup was in the upper layer. Specialists said the double-ceiling construction may have hidden the telltale ceiling stain that signals grease buildup.

Double-ceiling construction is not uncommon in Massachusetts, Notarianni said. “It creates a concealed space so the fire is allowed to burn undetected,” she said.

There were 280 restaurant fires in Massachusetts in 2005, the last year for which figures are available. They collectively caused 10 firefighter injuries, three civilian injuries, and $5 million in damages, according to the state Department of Fire Services.

Sixty percent of the fires started in the kitchen, with 5 percent, or 14 fires, starting in chimneys or grease-exhaust pipes.

Across the nation, firefighters responded to 8,520 fires in bars and restaurants between 2000 and 2004, according to the National Fire Protection Association. The fires killed three firefighters, injured 113 civilians, and caused $190 million in damage.

The kitchen was the most common place the grease fires started, accounting for 54 percent of the blazes.

Some type of cooking equipment was involved in 48 percent of the fires and 49 percent of the injuries. Chimneys or vents were responsible for 3 percent of the fires; grease hood and duct exhaust fans for 1 percent.

When it comes to weak regulations for grease-cleaning companies, Massachusetts is not alone. No states and only a few municipalities, including Corpus Christi, Texas, have instituted training and certification requirements since 1998, when the national codes were revised to include the training language for grease-inspection and cleaning companies.

Industry specialists say that if more state and local governments instituted training standards, more fires could be prevented and lives saved.

“The code was primarily created because the industry needed some standard,” said Robert M. Hinderliter, chairman of the training committee for the International Kitchen Exhaust Cleaning Association, which is pushing for higher industrywide standards.

“If they look at them and pay attention to them, it will make a major difference” in preventing fires.

More information at www.Boston.com.